The Chip Chase: How Europe Falls Short in Global Semiconductor Competition

Europe and the USA Seek to Attract Industry Specialists and Open Factories Capable of Manufacturing These Electronic Components Crucial for Their Economies

Just one year after conquering the planet with ChatGPT, the AI application designed by OpenAI engineers, CEO Sam Altman raises the bar even higher. As revealed by The Wall Street Journal, the young magnate from California is now focusing on constructing dozens of semiconductor factories worldwide. These semiconductors have become essential for ChatGPT's "neural" networks.

For this purpose, Altman met with officials and investors in the United Arab Emirates to present his plan, primarily to secure funding for building these factories, as noted by the American newspaper. The cost of this ambitious plan is estimated between 5 to 7 trillion dollars, nearly double Germany's GDP.

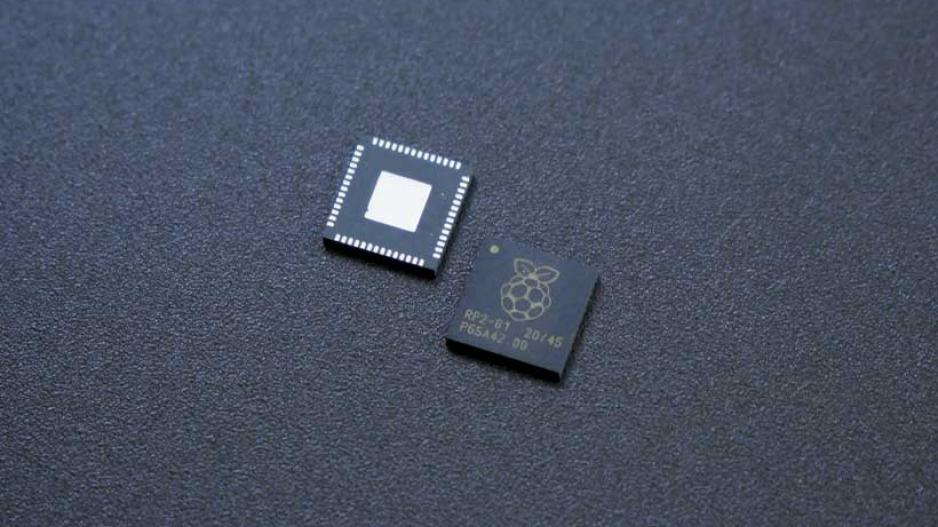

Altman's plan is not far-fetched. Building a new microchip factory costs tens of billions of dollars, but global semiconductor sales surpass half a trillion dollars annually. Advanced AI applications require immense computational power, and nothing will function in the cars and factories of the future without powerful semiconductors.

"This is a new industrial revolution," writes the German Handelsblatt. It's a revolution sufficient to ignite new competition between the United States, Asia, and Europe, which has been trying for several years to implement a new policy to catch up industrially in this sector. Europe has dedicated a 43-billion-euro investment plan, the European Chips Act, aiming to double its market share by 2030, which currently represents just 10% of global production.

Currently, semiconductors are essentially in the hands of Asia, which accounts for about 80% of global production capacity. Taiwan alone represents more than 60% of global production, led by the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the undisputed global leader in microchips, far ahead of South Korea's Samsung.

To reduce their dependence on the small island state, which is increasingly threatened by China, Europe and the USA seek to attract industry specialists and open factories capable of manufacturing these electronic components crucial for their economies.

Germany is expected to be the big winner of the "European Chips Act," hosting the largest semiconductor factories. In Dresden, TSMC will set up its first European factory by 2027, in collaboration with Dutch NXP Semiconductors and German Infineon and Bosch. An investment of 10 billion euros, half subsidized by Germany, with the Taiwanese giant contributing just 3.5 billion euros.

Berlin also did not hesitate to subsidize Californian Intel with another 9.9 billion euros for a total investment of 30 billion euros in Magdeburg. Intel's factory will be the largest semiconductor production facility in Europe and is expected to be operational by 2027. The German government plans to allocate another 20 billion euros to open more semiconductor factories in the country.

In the same context, French President Emmanuel Macron, after failing to convince Intel's boss Pat Gelsinger to invest in France, granted 2.9 billion euros for the construction of a new semiconductor factory by the Franco-Italian group STMicroelectronics near Grenoble. The total cost of this investment reaches 7.5 billion euros, with the remainder covered by American GlobalFoundries.

European officials, however, estimate that "domestic chip production" is not advancing in Europe as it should, and current plans are far from achieving the target of 20% of global semiconductor production in six years. "It is completely unrealistic," says CEO of Dutch semiconductor company ASML, Peter Wennink. "If we calculate Europe's share in chip production at 8% of global, significant more investments and many additional new factories are needed to reach the 20% target," Wennink emphasizes. "If Europe wants to achieve a 20% share in global semiconductor production by 2030, it will need at least three times the current capacity, or more likely four times," he explained.

"But with just 43 billion euros from the 'European Chips Act,' the EU will not go very far," writes Politico. "At least 500 billion euros are needed to achieve the 20% target."