A Bold Experiment in Work-Life Balance Begins in Germany

German Companies Test the Impact of a Shorter Workweek

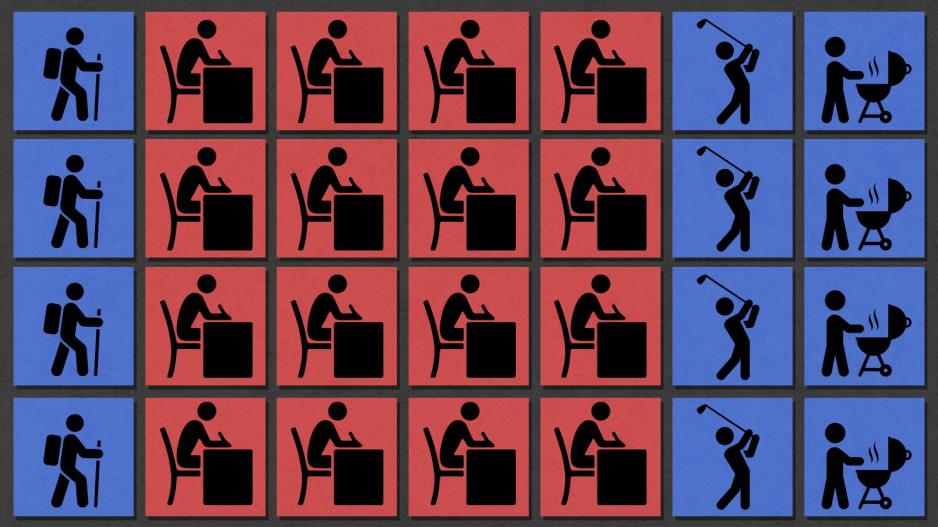

Starting yesterday, 45 companies and organizations across Germany embark on a six-month experiment to test the practicality of a four-day workweek. Employees participating in this trial will receive full pay despite working fewer hours, whether in the office or from home. This initiative is led by the management consultancy firm Intraprenör, in collaboration with the Non-Governmental Organization 4 Day Week Global (4DWG).

The move raises a pertinent question: how can a four-day workweek function effectively when many German businesses already face a shortage of specialized labor? Wouldn't it be more beneficial for workers to work longer, not shorter hours?

Proponents of the four-day workweek argue that this model could counter the skilled labor shortage by increasing employee productivity. They contend that people working only four days a week are more motivated and therefore more productive. Additionally, they believe that this schedule will attract more applicants who were previously unwilling or unable to work a traditional five-day week, thus potentially reducing the skilled labor shortage.

The four-day workweek has been trialed before. Since 2019, 4DWG has implemented such pilot programs in the UK, South Africa, Australia, Ireland, and the USA. Over 500 companies have participated in these initiatives, and the results appear to confirm positive outcomes.

Researchers from Cambridge and Boston report a 66% reduction in sick leave and nearly 40% of employees reported feeling less stressed after the experiment. Interestingly, the number of employees resigning from their jobs dropped by 57%. Perhaps most significantly, researchers noted an average increase in revenue of about 1.4%. At the end of the trial, 56 out of 61 participating companies stated they would continue the four-day workweek.

However, some experts question the broader applicability of these findings. Enzo Weber, a labor market specialist at the University of Regensburg and the Institute for Employment Research, criticizes the results of the pilot programs. He explains that only companies for which a four-day workweek makes sense applied to participate, suggesting that these firms are not representative of the entire economy. Weber also observes that the reduction in work hours affects not only the hours themselves but also processes and organization negatively.

Holger Schäfer from the German Economic Institute (IW Köln) agrees, believing that establishing a four-day workweek across the board could be counterproductive. "What at first glance seems sensible turns out to be problematic: if all companies adopt a four-day workweek, there will be a deficit in working hours," concludes the German expert. Despite these arguments, IG Metall, Germany's largest trade union, has long advocated for reduced working hours. In the steel industry, a 35-hour workweek has already been established.