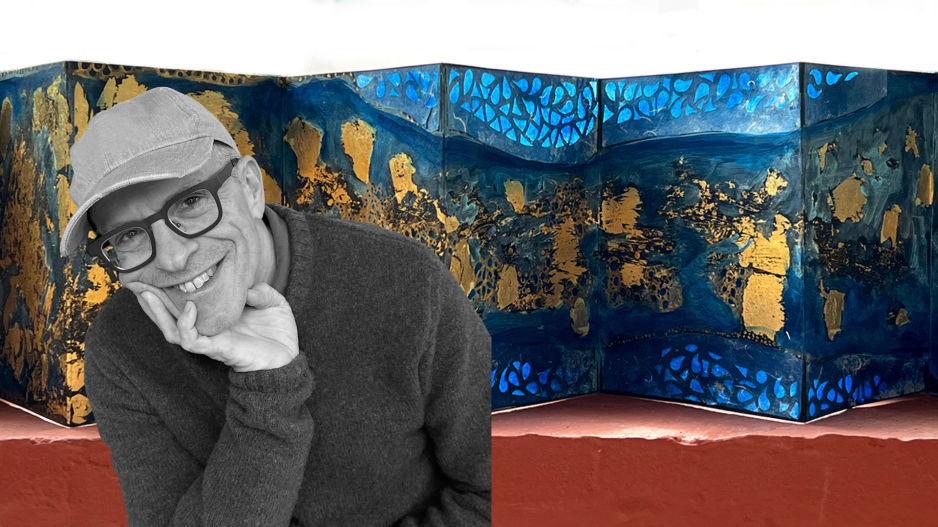

Bill Travis: Bringing the Past Into the Present Through Art and Photography

History, Art, and Desire Through the Lens of Bill Travis

Before becoming an acclaimed artist, Bill Travis was a tenured professor specializing in medieval sculpture at the University of Michigan, Dearborn. Since shifting his focus to art and photography in 2003, his work has been showcased in museums, galleries, and institutions worldwide, entering prestigious collections such as Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, The New York Public Library, and the Cabinet des Estampes in Paris. His artist books have found homes in institutions like The Library of Congress, Yale, and Harvard, reflecting his deep engagement with the tactile and poetic nature of art.

In this interview, we delve into Travis’s unique artistic vision, where light, touch, and historical depth converge. His creations explore themes of love, desire, and the breakdown of democratic norms, often drawing inspiration from literary giants like Walt Whitman and Cavafy. From handmade transparencies to luminous books crafted from mother of pearl and gold, Travis invites audiences to experience art not just visually but physically, forging an intimate connection between artist and viewer.

With an eye toward the Hellenic world and a special interest in Cyprus, Travis speaks about his latest projects, including works inspired by Plato and the Acritic songs, as well as his aspirations to visit Cyprus and collaborate with local artists. His reflections on creativity, history, and craftsmanship make for a compelling conversation about the transformative power of art.

You’ve increasingly focused on creating artist books. What draws you to this medium, and how does it differ from presenting your work in traditional gallery or museum settings?

Most work you see in a gallery or museum can be hung any number of ways, even if the work originated as a series, but book art is different. There's a defined sequence, and that constraint opens up a wealth of possibilities. For instance: How does each page visually rhyme with the facing page? How do these rhymes extend throughout the book? How do you hold attention on each page and at the same time invite the reader to discover what's coming next? Constraints are wonderful things. They stimulate the imagination.

Of course, there's also that complex relationship to a text. If you're just illustrating words, the art is not very interesting, but if the words and the art come together, like lovers, you forge a new whole. Sometimes I start a book with lots of imagery and bring in words only after the tenth page or so. I think of this as creating an atmosphere that hints at the text before you even encounter it. Sometimes I quote a text exactly; other times I intentionally take it out of context; or I excerpt only the briefest passage. The text is never sacrosanct. I take it on as an additional challenge, to bend and reshape in the interest of creating something new. I hope that one day artists might use my own work the same way. Everything you make is just a stepping stone. You build.

Another thing about book art: you hold it in your hands. It's one of the most tactile art forms and that is something I always take care to emphasize. Every page invites you to experience a different sensation on your fingers, from mother of pearl to gold, sandpaper, silk, wax, various paper types, and degrees of relief. The emphasis on touch is not an end in itself. It flows directly from the subject matter: love, desire, longing... If you touch one of my books, you're already going beyond what the eye can see. You're reading it with your body.

Bill Travis, Uma carta (a letter; after Francisco Correa Netto), paper with gold and mixed media; 20 pages; 7 x 6 ¼ in. 2023. Collection: Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon.

Once you put a book down, it goes to sleep, and only awakens when you take it up again. I love the idea of an art form that seems to live and breathe in this way. There's an added advantage: since a book is more often closed than not, it also preserves its original appearance much better than a fresco or oil painting might, for instance. One of the most thrilling artistic experiences in my life was holding a Middle Byzantine illuminated manuscript, which looked and felt almost identical to the time it was created a thousand years ago, with its pure, brilliant colors and a vellum so soft to the touch you could mistake it for ivory.

Day view of backside: Bill Travis, Ballade des dames du temps jadis (Ballad of women from yesteryear; after François Villon), paper with gold and mixed media; 6 3/4 x 27 in. when fully unfolded. 2023. Collection: Library of Congress.

Maybe most important, it's just the two of you when you hold a book. Try that with a painting hanging in a museum! Book art establishes intimacy. We live in an age of public art; a book brings us back to a more private sphere.

Backlit view of the same book, front side.

What can we expect from your work in the future?

I've been working for years on themes from different periods of Greek art and philosophy. Let me tell you about a fifteen-foot scroll I recently made based on Plato's Phaedrus.

Opening segment: Bill Travis, Fragments, scroll with mixed media; 1 ft. x 15 ft. when fully open. 2023.

While most ancient Greek texts have come down to us as fragments, Phaedrus has miraculously survived intact. What I set out to do was to turn the text back into a fragment, isolating several words or phrases and deleting others, allowing coherence to reemerge only at the very end with a few complete sentences.

Detail from the same book.

Detail from the same book.

The willful distortion has an expressive purpose: the choppy text confuses us at first, but by the time we reach the end, we understand that the subject is in fact the young man's confusion. He’s in love, Plato writes, but doesn’t understand and sees only himself.

Detail from the same book.

The book’s physical make-up builds on the idea of fragmentation, as different paper types and sizes suggest a reassembled text. There are also intentional gaps. The illustration, meanwhile, moves from inchoate ink blots and abstract designs to figurative art when we meet the youth himself.

How has Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s philosophy on art and beauty influenced your work, particularly in projects like Mein Freund that explore themes of male beauty and intimacy?

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the "father" of art history, played a key role in restoring Greek art to its lofty role in the West. A very gay and very erudite German living in the eighteenth century, Winckelmann fell in lust with a handsome young nobleman, and, in 1763, sent him a letter arguing that anyone who truly loves art must also love male beauty. He used Greek art to prove his point.

Bill Travis, Mein Freund, hanging scroll with mixed media; 49 x 10 1/4 in. when fully open. 2024.

My artist book, which I call "Mein Freund" (my friend), quotes an excerpt from Winckelmann's letter. Abalone and mother of pearl make the book unusually luminous. At night, the light becomes yet more dramatic as images on the page darken and windows of shell glow through the cutouts.

Detail of same book, backlit in early evening.

The book hangs from the ceiling so you can walk around it. Again, you read the book with your body.

There's so much more I want to do around the Hellenic world. I'm currently working on a project after Cavafy which deals with longing, tenderness, and nostalgia, with large and heavy pages designed to exalt these feelings. Let me show you a page that's about forty inches high and--put together as a mosaic of wood, mother of pearl, gold, and mirrors--weighs in at a few pounds. So the book is not made to be read in a traditional sense, and I feel that the physicality, the shimmering light, and the sheer weight slow the "reader" down and turn the book into something really meditative. Who knows? Perhaps this actually brings us closer to Cavafy.

Bill Travis, work in progress, for a poem by Constantine P. Cavafy; this page is 40 inches high; photo-based image with gold, mirrors, mother of pearl, and acrylic paint.

Are there any upcoming projects or exhibitions, and do you have plans to visit Cyprus to showcase your art or collaborate with local artists?

Cyprus is an area of special interest to me. I recently learned about Acritic songs, from the eastern frontier of the Byzantine Empire, with their soaring language and hidden homoeroticism (at least, as I interpret them). I cannot read Greek, unfortunately, but these songs are powerful even in translation. Here is a passage in the original, from a twelfth-century work by Digenes Akritas, later recognized as a protector of Cyprus:

Ὡς δράκοντες ἐσύριζαν καὶ ὡς λέοντες ἐβρυχοῦντα

καὶ ὡς ἀετοί ἐπέτουντα, καὶ ἐσμίξασιν οἱ δύο·

καὶ τότε νὰ ἰδῆς πόλεμον καλῶν παλληκαρίων.

Και ἀπὸ τῆς μάχης τῆς πολλῆς κροῦσιν διασυντόμως·

καὶ απὸ τὸν κτύπον τὸν πολὺν καὶ ἀπὸ τὸ δὸς καὶ λάβε

οἱ κάμποι φόβον εἴχασιν καὶ τὰ βουνιὰ ἀηδονοῦσαν,

τὰ δένδρη ἐξεριζὠνουντα καὶ ὁ ἥλιος ἐσκοτίσθη.

Tὸ αἷμαν ἐκατέρεεν εἰς τὰ σκαλόλουρά των

καὶ ὁ ἵδρος τους ἐξέβαινεν ἀπάνω ἀπ' τὰ λουρίκια.

Ἦτον <καὶ> γὰρ τοῦ Κωνσταντῆ γοργότερος ὁ μαῦρος,

καὶ θαυμαστὸς νεώτερος ἦτον ὁ καβελάρης·

I would love to visit Cyprus. I want to see the art in its original setting and would be delighted to exhibit my own work. I want to see the landscape. And I especially want to collaborate with local poets and artists. Growing up in Los Angeles, as I did, can desensitize you to the long arc of history, but in my case, I think it made me even more responsive to cultures with long and complex traditions. The way creative people in Cyprus have referred to these traditions, while also making something new and exciting, is something completely in tune with my sensibility.