German Industry: The End of an Era

“We Are Getting Poorer Because We Don’t Have Growth. We’ve Fallen Behind,” German Finance Minister Said

Last fall marked the final chapter in the history of a pipe factory in Dusseldorf. It concluded a 124-year journey that began in the era of German industrialization, survived two world wars, but could not withstand the aftermath of the energy crisis. Over the last year, many such factories have closed, highlighting a painful reality for Germany: its days as an industrial powerhouse may be nearing an end.

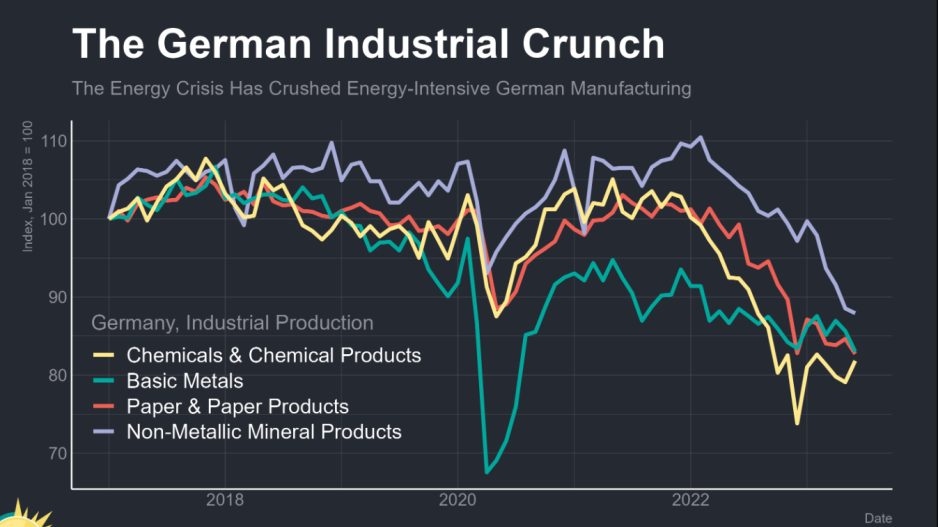

Manufacturing output in Europe's largest economy has been declining since 2017, and the fall is accelerating as competitiveness erodes. "There isn't much hope, to be honest," said Stefan Klebert, CEO of GEA Group AG, a machinery supplier rooted in the late 1800s. "I'm not sure we can stop this trend. A lot would need to change, and quickly."

The foundations of Germany's industrial engine are falling like dominoes. The US is distancing itself from Europe, competing for climate investments. China is becoming a bigger rival, no longer an insatiable buyer of German products. The final blow for some heavy manufacturers was the end of copious amounts of cheap Russian natural gas.

Alongside global instability, political paralysis in Berlin exacerbates long-standing internal issues like workforce aging and bureaucracy. The once-strong education system symbolizes a chronic lack of investment in public services. The Ifo research institute estimates that declining mathematical skills could cost the economy about 14 trillion euros ($15 trillion) in output by the end of the century.

In some cases, the industrial downturn occurs in small steps, like reduced expansion and investment plans. Others are more visible, such as changing production lines and staff cuts. In extreme cases – like the Vallourec SACA pipe factory, once part of the defunct industrial giant Mannesmann – the consequence is permanent closure.

Germany still boasts a roster of small, agile manufacturers, and institutions like the Bundesbank reject the idea that full deindustrialization is imminent. However, with reforms stalled, it's unclear what will slow the decline. "We are no longer competitive," Finance Minister Christian Lindner said at a Bloomberg event. "We are getting poorer because we don't have growth. We've fallen behind."

The weakening of industrial competitiveness threatens to plunge Germany into a downward spiral, according to Maria Röttger, head of Michelin for Northern Europe. The French tire manufacturer is closing two of its German plants and reducing a third by the end of 2025, affecting over 1,500 workers. American competitor Goodyear has similar plans for two facilities.

One of the hardest-hit sectors is chemicals – a direct result of Germany losing cheap Russian natural gas. As the transition to clean hydrogen remains uncertain, nearly one in ten companies plans to permanently stop production processes, a recent VCI industry association survey shows. BASF SE, Europe's largest chemical producer, is cutting 2,600 jobs, and Lanxess AG is reducing its staff by 7%.

German bureaucracy also fails to keep pace, even when companies are ready to invest. GEA installed solar power at a factory in Oelde, western Germany, where it manufactures equipment to separate cream from milk. It applied for power supply permits last January, two months before construction began, and is still waiting for approval – nearly two years after the project started.

China now poses various challenges to Germany. Beyond its strategic shift towards advanced manufacturing, the slowdown of the Asian superpower's economy further reduces the demand for German products. At the same time, cheap competition from China worries industries vital for Germany's climate transition – not just electric cars.

The Bundesbank concluded in a September report that a gradual decline in manufacturing isn't alarming. Such a trend could spell the end of the road for more basic manufacturers, like the Dusseldorf pipe factory. Freitag, a member of the factory's works council, is now helping prepare the 90-hectare site for sale. Much of the equipment will end up in a scrapyard, which "breaks my heart and brings tears to my eyes," he said poignantly.